DHAKA: When Muhammad Yunus assumed leadership of Bangladesh’s interim government on 8 August 2024, expectations were unusually high. He was not just another political figure. He was a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He was the global face of microfinance. He was the man who once promised to “send poverty to the museum.”

Many believed that a respected economist with international credibility could steady a shaken nation. After political upheaval and the fall of the previous administration, the country needed stability, reform, and confidence. Yunus appeared to offer all three.

Eighteen months later, the debate is no longer about hope. It is about outcomes.

The Economy Under Strain

Economic management became the central test of his leadership. Data cited by economists suggest that nearly three million additional people slipped below the poverty line during this period. Whether temporary or structural, this rise deeply affected public perception.

Private sector investment declined. As a share of GDP, it fell from around 24 percent in mid-2024 to 22.48 percent by mid-2025. This marked one of the lowest levels in decades. Investment is a signal of business confidence. When it drops, it often reflects uncertainty about policy, regulation, and future growth.

Public investment also slowed. Implementation of the Annual Development Programme (ADP) recorded its lowest pace in ten years. Between July and November of the fiscal year, progress hovered at around 11.5 percent. Delays in public projects mean fewer jobs and slower infrastructure expansion.

Inflation remained a heavy burden. At one stage, it stood at about 8.5 percent, while wage growth trailed slightly below that rate. This gap reduced real income. For ordinary families, this meant less purchasing power and greater financial anxiety.

Policy interest rates stayed high to control inflation and stabilize reserves. But higher borrowing costs discouraged private credit growth. Industrial output felt the pressure. Employers delayed expansion plans. Job creation slowed.

These trends created the perception of stagnation rather than recovery.

Debt and Banking Fragility

By the end of fiscal year 2024–25, total government debt—domestic and foreign—had reached approximately 2.25 trillion taka. In just six months, significant borrowing occurred from both local banks and foreign sources. Critics argue that the next elected administration will face limited fiscal space because of this accumulation.

More alarming was the condition of the banking sector. By September 2025, non-performing loans reportedly reached over 6 lakh 44 thousand crore taka, accounting for more than one-third of total distributed loans. Such a high default ratio undermines trust in financial institutions. It also weakens credit flows to productive sectors.

A fragile banking system does not only affect investors. It affects depositors, small businesses, and ordinary citizens. Confidence, once shaken, is difficult to restore.

The Reserve Question

In his farewell remarks, Yunus highlighted the growth of foreign exchange reserves, which reportedly reached around 34 billion US dollars. He presented this as evidence of stabilization.

However, critics questioned the method behind the numbers. They argued that reserve growth was achieved partly through import compression and reduced energy spending. If industrial imports decline sharply, reserves can temporarily rise. But domestic production may suffer.

Remittances played a crucial role in maintaining stability. Food inflation showed modest improvement at certain points. Yet economists remind policymakers that reserves are a means, not an end. Employment, productivity, and sustainable growth are the ultimate measures of economic health.

The debate is therefore not about the number itself. It is about the trade-offs involved.

Governance and Institutional Questions

Economic performance was only part of the narrative. Governance and transparency also came under public scrutiny.

Several institutions associated with Yunus, including Grameen Bank, reportedly received policy advantages during this period. Tax exemptions were granted. The government’s shareholding in the bank declined from 25 percent to 10 percent. Other Grameen-affiliated ventures secured regulatory approvals with notable speed.

Critics questioned whether these actions created a perception of conflict of interest. Supporters argued that these institutions have long contributed to social development and deserved facilitation.

Meanwhile, legal cases previously filed against Yunus related to labor and financial matters were dismissed during his tenure. Observers debated whether due process was fully transparent. In addition, the interim government held limited open press conferences. Media engagement appeared controlled and selective.

Reform commissions were formed. Reports were compiled. Yet visible structural transformation—especially in decentralization, local governance strengthening, and accountability systems—remained limited, apart from the successful organization of a peaceful election.

Law, Order, and Social Stability

Perhaps the most sensitive issue was social stability. Reports of mob violence, vandalism of religious sites, and intimidation of journalists drew national and international attention.

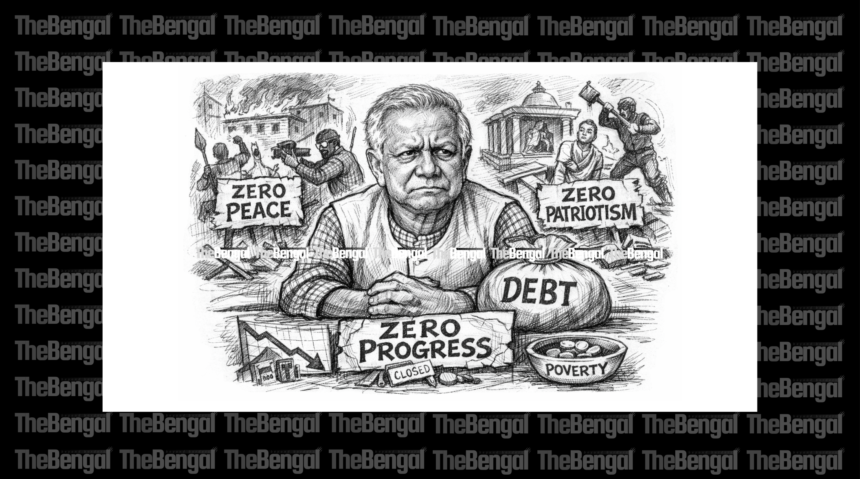

For a leader globally associated with peace, such developments created a sharp contrast. Yunus has long championed his “Three Zeros” vision: zero poverty, zero unemployment, and zero carbon emissions. During his time in executive power, however, poverty pressures increased and unemployment concerns persisted.

The gap between vision and statecraft became a central talking point.

The Meaning of the “Three Zeros”

Critics have framed the period as “Zero Peace, Zero Patriotism, Zero Progress.” It is a politically charged phrase. Yet it reflects genuine anxieties among segments of the population.

“Zero Peace” points to rising social tension.

“Zero Progress” refers to weak investment and economic slowdown.

“Zero Patriotism” reflects claims that institutions and national symbols were not defended strongly enough during episodes of unrest.

Supporters counter that Yunus inherited structural fragilities and limited time. They argue that stabilizing reserves and conducting a credible election were significant achievements under challenging circumstances.

The truth may lie between these positions.

Leadership and Legacy

History often judges leaders by outcomes, not intentions. Yunus entered office with rare credibility. Few leaders combine global admiration, moral authority, and domestic goodwill. He had a window for reform that comes only once in a generation.

Whether that opportunity was constrained by political realities or missed due to strategic hesitation will remain debated.

What is clear is that governing a nation is different from leading a social movement. Economic theory must confront political complexity. Moral authority must operate within institutional limits.

As Bangladesh moves forward under new leadership, it carries both economic challenges and unresolved institutional questions. The legacy of these 18 months will shape future policy debates.

For Muhammad Yunus, the global advocate of social business and the architect of the “Three Zeros,” the experience offers a sobering lesson. Vision inspires. Governance tests. And history measures the distance between the two.