DHAKA: Bengali nationalism is often misunderstood. Some reduce it to poetry, music, and nostalgia. Others dismiss it as outdated in a globalized world. Both views are wrong. Bengali nationalism was born as a political force, and it continues to matter because the political conditions that created it have not disappeared.

At its heart, Bengali nationalism is about power— who controls language, whose culture is recognized, and whose identity is allowed to exist with dignity.

The origins of Bengali nationalism lie in resistance to domination. In Pakistan, the attempt to impose Urdu as the sole state language was not a neutral policy choice. It was a political project designed to marginalize the Bengali majority. The Language Movement of 1952 was therefore not cultural symbolism. It was a direct challenge to state power. When students were killed for demanding recognition of Bangla, language became a matter of life and death.

That struggle did not end in 1952. It continued through economic discrimination, political exclusion, and military repression, culminating in the Liberation War of 1971. Bangladesh was not created merely as a new state. It was created as a rejection of cultural subjugation and political denial. Bengali nationalism was its ideological foundation.

More than five decades later, Bangladesh exists as an independent country. Yet the relevance of Bengali nationalism has not faded. Instead, it has entered a new and more complex phase.

Today, the threat is not an external language imposition. It is internal erosion. When democratic institutions weaken, when dissent is silenced, and when history is selectively remembered, the original spirit of Bengali nationalism is challenged. The question is no longer whether Bangla is recognized as a state language. The question is whether the values born from the language movement—pluralism, justice, and popular sovereignty— are being upheld.

Bengali nationalism in Bangladesh was historically secular and inclusive. Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and indigenous communities all contributed to its formation. Any attempt to redefine the nation through religious exclusivity directly contradicts that legacy. When nationalism is reduced to slogans without substance, it loses its moral authority.

This is why Bengali nationalism still matters politically. It serves as a standard against which state power must be measured. It reminds citizens that the nation was not created to serve elites, but to protect the rights and dignity of ordinary people.

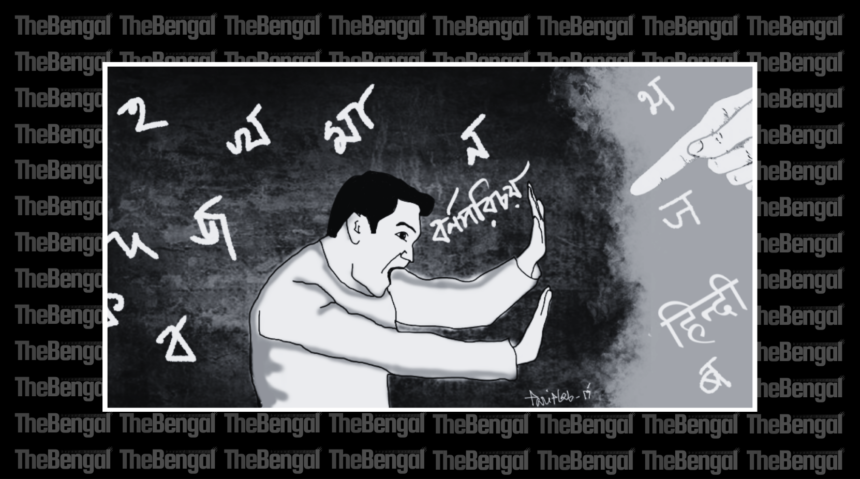

Across the border in India, Bengali nationalism exists under very different conditions. It does not operate within a sovereign Bengali state. Instead, it functions inside a multilingual federal system where power is increasingly centralized. In this context, Bengali nationalism is less about independence and more about resistance to cultural and linguistic homogenization.

West Bengal, Tripura, and parts of Assam have long histories of Bengali cultural dominance in literature, education, and public life. Yet recent political developments have unsettled that position. Language has once again become a political battleground. The privileging of Hindi, the rewriting of historical narratives, and the framing of linguistic communities as outsiders have created anxiety among many Bengalis.

Here, Bengali nationalism is often misrepresented as regional arrogance or political obstruction. In reality, it is a defensive response. When people feel their language is being pushed to the margins, asserting identity becomes an act of survival. This is not unique to Bengalis. It is a pattern seen across the world wherever central power attempts cultural uniformity.

Importantly, Bengali nationalism in India has largely remained constitutional. It expresses itself through electoral politics, cultural institutions, and civil society, not armed resistance. This distinction matters. It shows that linguistic nationalism does not automatically threaten state unity. In fact, suppressing it often creates deeper instability.

Critics frequently warn that nationalism leads to division. History shows the opposite is often true. Denial of identity fuels resentment. Recognition creates stability. Bengali nationalism, when rooted in democratic values, strengthens pluralism rather than undermining it.

Another uncomfortable truth must be acknowledged. Globalization has not erased power hierarchies. English dominates education, employment, and digital spaces. Global media privileges certain cultures while sidelining others. For Bengali speakers, especially those outside elite urban centers, this creates a new form of marginalization. Cultural confidence becomes political capital.

This is why dismissing Bengali nationalism as outdated is intellectually lazy. The world has not moved beyond identity politics. It has simply reorganized it. Those without power are told to be universal. Those with power define what universal means.

Bengali nationalism offers a counter-narrative. It asserts that local cultures matter. That language is not a barrier to progress. That history should not be rewritten to suit political convenience.

At the same time, Bengali nationalism must confront its own limitations. It cannot afford to become exclusionary. It must make space for indigenous communities, migrants, and linguistic minorities. A nationalism that reproduces the injustices it once fought against loses its legitimacy.

The future of Bengali nationalism depends on this balance. It must remain politically alert without becoming authoritarian. Proud without becoming hostile. Rooted without becoming rigid.

For Bangladesh and Eastern India, Bengali nationalism does not demand political unity across borders. It does not erase national sovereignty. What it offers instead is a shared moral and cultural language—one that resists erasure, questions power, and insists on dignity.

In a region shaped by partitions, wars, and shifting alliances, this shared consciousness matters. It reminds people that borders may divide states, but history, language, and memory continue to connect societies.

Bengali nationalism still matters because the struggle it represents is unfinished. As long as language is politicized, culture is controlled, and identity is negotiated through power, the idea will remain relevant.

It is not a relic of the past. It is a political resource for the present.