DHAKA: The citizenship debate in Assam is often presented as a regional issue. It is framed as a local concern about land, resources, and cultural preservation. But for millions of Bengalis across borders, this debate feels deeply personal. It touches old wounds of displacement, identity, and survival. It also raises troubling questions about who truly belongs in South Asia.

Assam is not isolated from history. Its demographic reality was shaped by colonial policies, economic migration, and political decisions taken far away from the Brahmaputra Valley. Yet today, the burden of that history is being placed on ordinary people—many of them Bengali-speaking—who are now asked to prove their right to exist.

This is why Bengalis in West Bengal, Tripura, Bangladesh, and even in the diaspora watch Assam with unease. What is unfolding there is not just about citizenship papers. It is about dignity, fear, and the fragile promise of equal rights.

A History That Cannot Be Ignored

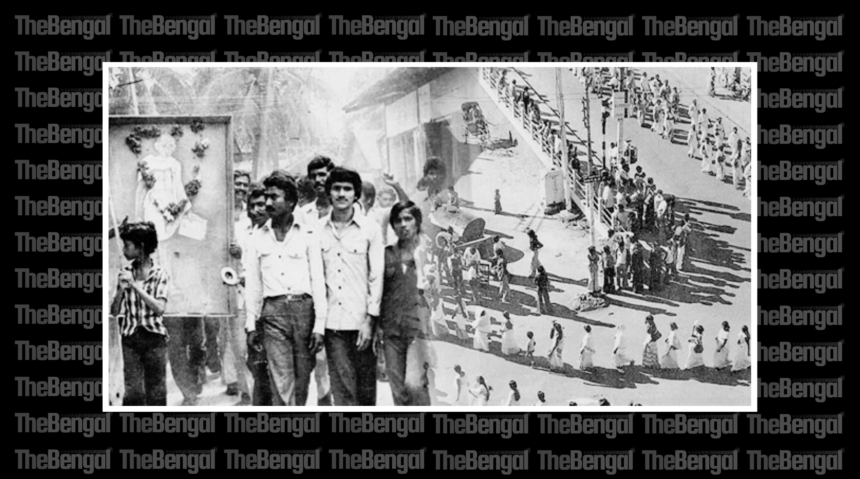

Migration into Assam did not begin yesterday. During British rule, Bengali clerks, teachers, and administrators were brought to Assam to run the colonial system. At the same time, Bengali Muslim peasants from East Bengal were encouraged to settle on fertile but sparsely populated lands. These movements were policy-driven, not illegal.

After 1947, Partition changed everything. Borders were drawn, but people were already living where they were. Many Bengali Hindus fled communal violence in East Pakistan and settled in Assam and other northeastern states. Later, the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War caused another wave of refugees.

These were not choices made lightly. They were acts of survival.

Yet, decades later, their descendants are being asked to prove their ancestry with documents that many poor families never possessed or could preserve. For Bengalis elsewhere, this feels like history is being selectively forgotten.

The NRC and the Politics of Fear

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) was meant to identify undocumented immigrants. In theory, it was a legal exercise. In reality, it became a humanitarian crisis.

Nearly two million people were left out of the final NRC list in 2019. Among them were daily wage workers, farmers, women, and elderly people. Many were Bengali-speaking Hindus and Muslims. Some had lived in Assam for generations.

The fear did not stop at exclusion. Detention centers, legal uncertainty, and social stigma followed. Families were torn apart by paperwork. Anxiety became a part of daily life.

For Bengalis across borders, the NRC sent a chilling message. It suggested that citizenship could become conditional. That language, surname, or perceived origin could make someone perpetually suspect.

Language, Identity, and Othering

At the heart of Assam’s debate lies a deeper issue: language as identity.

Bengali speakers in Assam are often seen as outsiders, even when they are Indian citizens by law. The fear of cultural erosion among Assamese communities is real and must be acknowledged. Every community has the right to protect its language and heritage.

But protection should not turn into exclusion.

When a language becomes a marker of loyalty, democracy suffers. Bengalis elsewhere recognize this danger because they, too, have faced attempts to reduce identity to a single label. Across South Asia, language politics has often led to division, not harmony.

The worry is not about Assam alone. It is about the normalization of linguistic nationalism overriding constitutional citizenship.

Why Bengalis Beyond Assam Feel Threatened

For Bengalis in West Bengal, the Assam experience feels uncomfortably close. Many families share roots across present-day borders. Migration between Bengal regions was once natural and continuous.

In Tripura, where Bengalis are now a majority, similar anxieties exist. Could citizenship debates be weaponized elsewhere? Could history be reinterpreted again?

In Bangladesh, the issue is followed with concern and sensitivity. While Bangladesh rejects accusations of large-scale illegal migration today, it cannot ignore the human cost of labeling people as foreigners decades after borders were sealed.

For the Bengali diaspora, especially in Europe and the Middle East, Assam represents a warning. If citizenship can be questioned so easily, how secure is belonging anywhere?

Hindus, Muslims, and a Shared Anxiety

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Assam’s citizenship debate is the idea that it affects only one community. In reality, Bengali Hindus and Muslims both face uncertainty.

While political narratives often frame the issue through a religious lens, the NRC experience showed that documentation, not faith, determined fate. Poor Hindus were excluded. Muslims with valid claims were questioned.

This shared vulnerability should have encouraged solidarity. Instead, it often deepened divisions.

Bengalis watching from outside see this clearly. They understand that when citizenship becomes selective, no group remains permanently safe.

Legal Citizenship vs Social Acceptance

Even those who make it through legal processes often face social exclusion. Being declared a citizen on paper does not always mean being accepted in society.

Children face discrimination in schools. Families feel pressure to hide their language in public spaces. This silent erosion of dignity is difficult to measure, but deeply damaging.

For Bengalis everywhere, this raises a painful question: Is citizenship only about documents, or is it also about belonging?

A democracy must answer this carefully.

The Risk of Dangerous Precedents

What happens in Assam does not stay in Assam.

If large populations can be asked to reprove citizenship decades after independence, similar exercises could emerge elsewhere. If language becomes grounds for suspicion, pluralism weakens.

Bengalis across borders are not opposing Assam’s right to protect its culture. They are questioning methods that create fear instead of trust.

History shows that identity-based exclusion rarely ends where it begins.

A Call for Empathy and Balance

Assam’s concerns deserve respect. So do the fears of indigenous communities. But solutions must be humane, inclusive, and constitutional.

Citizenship should not be a tool of anxiety. It should be a guarantee of rights.

For Bengalis across borders, the Assam debate is a reminder that identity in South Asia remains fragile. Borders may be fixed, but belonging is still contested.

The challenge before India—and the region—is to ensure that citizenship strengthens unity rather than deepens division.

Only then can the promise of democracy feel real to all.